2000 BC SCIENCE OF AEGEAN DISTILLATION

AND ORIGIN

by

Maria Rosaria Belgiorno

Nicosia 2022

2000 BC SCIENCE OF AEGEAN DISTILLATION

AND ORIGIN

by

Maria Rosaria Belgiorno

Nicosia 2022

“Αισθητική της ομορφιάς”

Is it logical to ask if the aesthetic perception of perfume is to be connected to the perception of smells that give olfactory pleasure, in the same way in which the vision of beauty is connected to the harmonic representation of shapes and colours, and music is related to the harmony of composite notes that can express the different states of the human soul? Are music, perfume and figurative art really connected to each other according to the Pythagorean canons of harmony that should generate pleasure, therefore happiness in the human soul? Simply put, does the perception of harmony create a feeling of pleasure?

Etymologically, the term àesthesis does not have anything to do with beauty, that is something that respects pre-established standards of perfection, but with perception, sensitivity: obviously not that of an individual but that shared by many if not by all. In common language the term àesthesis takes on many meanings, but its interpretation mainly concerns the theoretical aspect and the historical anamnesis of its evolution.

In practice, there are several questions about: what is aesthetics? When was aesthetics born? Is it something that manifests itself as a pleasant sensation in a particular moment of human evolution? Is it part of our DNA? Is the perception of beauty and goodness a recent acquisition or it is a characteristic of the human species?

It is difficult to give an exhaustive answer. But we believe that the perception of beauty and goodness is the result of a long journey through countless negative and positive experiences that have helped to shape the aesthetic sense and have determined its rules. Obviously, the different experiences and the different context in which aesthetics has evolved have created some "artistic" differences that broadly reflect the chronological belonging and geography of the places.

In our case it seems that Aegean aesthetics had a sort of acceleration during 2000 BC, manifesting its canons in a powerful way in the second half of the second millennium BC, directly involving the world of terrestrial and marine nature, in a completely different way from the mythological and celebratory world of other civilizations that faced the Mediterranean as the Mesopotamians and Pharaonic Egypt. A world rich in colours and scents realistically represented in every artistic elaboration where the attention of the beholder is captured by the polychromy and vivacity of the representations that recall not only the visual and olfactory memory, but also the colours and sounds of the surrounding environment. Nature is always present in the Aegean representations, even when the human figure takes on the role of the protagonist and the clothes are a refined intertwining of colourful fabrics and even gestures can recall dance steps as if the scene were accompanied by a well-known musical background.

We are faced with an aesthetic quest for its own sake, far from being celebratory, whose cultural anamnesis brings us back to the Cycladic art of the Early Bronze age, which had transformed music into an artistic expression, represented in the alabaster “idols” playing musical instruments. The result was a minimalist art that expressed in highly evocative essential lines, symbolizing different artistic figurative and musical expressions. Often, we wonder if they were artistic expressions created to satisfy one's own or others' aesthetic sense. But what seems certain is that the Aegean market, which included the small and large islands and the Peloponnese, required artefacts not only made of precious materials, but made with “art ”. This suggests that the cultural environment had its weight in their realization, confirming that the acquisition of the aesthetic sense and the consideration of the artistic artefacts were closely linked not only to the pleasure that they can arouse in the people, but also to the cultural heritage and local traditions.

The “οσμές”

In this complex cultural landscape in which beauty had already assumed sophisticated and essential canons, a hedonistic pleasure linked to taste and smell is born. We know that the two senses are inseparable since both arrive directly to the brain, immediately generating a return of pleasure or rejection, which is recorded creating an almost indelible memory. It is at this point that we ask ourselves what it means to wear a perfume and entrust ourselves in ephemeral olfactory notes behind which we hide faults and exalt our most intimate perception of pleasure.

Whereas the sense of smell is considered to be the most important human sense, to whom we owe much of the survival of our species, I wonder if the evolution of olfactory perception has followed an evolutionary path similar to the one that led to music and to the representation of the surrounding world, in terms of universally recognized art forms, whose harmony is mainly based on the fusion and agreement of the Pythagorean notes, be they lines, colours or sounds. The concept of harmony, aesthetic sense and its enjoyment is a Pythagorean concept based on the agreement between them of "celestial" notes such as those that perfectly govern the movement of celestial bodies and regulate the complex laws of nature.

But Pythagoras lived in the 6th century BC, a period in which the Greek civilization had begun the path towards the utmost consideration towards àesthesis. Although, looking at the artistic testimonies of the Minoan-Mycenaean world, it seems that this path began centuries earlier.

Basically, Septimio Piesse's identification of olfactory notes with musical notes in 1788 suggests the key to understanding the exclusive path of the Aegean aesthetic sense, which seems to have played a preponderant role in the evolution of goodness perception understood in a broad sense.

From Pythagoras to Piesse, from celestial bodies to musical notes from natural fragrances to the composition of a perfume or a melody, or to the representation of nature in its perfect coloristic accords, we are faced with the same phenomenon that creates visual pleasure in man olfactory or acoustic of an artistic composition that suits our aesthetic sense. Another aspect of the world of smell, concerns the short uncontrolled path of our will that makes the smell from the nose to the brain centres involved in emotions and memory (the amygdala and the hippocampus). Even before having the exact olfactory perception, our brain has already recognized its origin by recalling any emotions from the past. In the same way we recognize a musical motif, without remembering its name or a place by seeing its representation.

The complex and versatile Aegean art seems to address these extraordinary evocative faculties embodying the aesthetic values of their civilization, representing an idealized world closely linked to the surrounding reality. In this respect, the decorations of flowers and plants, fully recognizable, remind us of the fashionable fragrances of the time, perhaps not by chance painted on the vases destined to produce and preserve them.

The “απόσταξη”

Distillation is much more than an alembic process that the Arab propaganda shared like a Muslim invention. It is a technological process that has a basic importance in the evolution of science and human knowledge. Its story started much earlier than many other inventions, and its discovery/knowledge involved since the beginning all the fields of science, its evolution and research.

The physical phenomenon that causes vapor to condense into liquid when passing from a hot to a cold temperature was probably found much earlier than the invention of metals, but the ability of distillation to separate materials from each other was a gradual later discovery that passed through several stages. It is very likely that the first use was to recover fermented liquids that were no longer usable, obtaining drinks with an interesting and intoxicating flavour, which gave a pleasant sense of well-being. Logically, they were experiences of direct distillation carried out using common pottery, earth mixtures, leaves and marsh reeds, which paved the way for the production not only of alcoholic beverages but also of pharmaceutical compounds, perfumes, industrial oils, and fuels. There is a long list of distillation engagements without which today, our life would not be the same. Just we can estimate the difference in terms last in time before and after the documented experience of distillation.

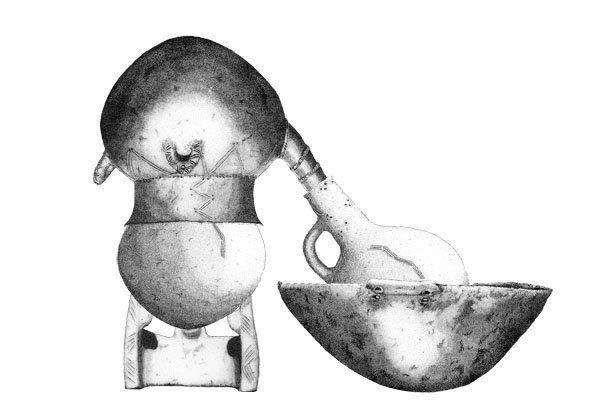

This research aims to reconstruct the techniques utilized in the 2nd millennium Aegean, utilizing, and expanding the suggestions that from Mesopotamia were filtering around the coasts of the Mediterranean. Studying and examining the functional characters of some vessels, whose typology appears around the turn of the second millennium BC, we realized that the knowledge on the subject was much more advanced than we expected to be. After a preliminary historical-geographical overview, the research points in the examination of the archaeological data and ceramic typologies possibly involved in processing organic and inorganic materials.

Protocols of experimental archaeology with the replicas of the originals and the botanical ingredients mentioned in the linear B tablets, have been employed to demonstrate the elaborated 2nd millennium BC technology and knowledge that anticipates by many centuries the physical and chemical/alchemical information of which there is ample testimony from the third century AD.

The evolution of the science of distillation seems to concentrate in the Aegean area in the second millennium BC, with the invention of peculiar distillation equipment, direct precursors of retorts, stills and glass serpentine that are still today the characteristic instrumental repertoire of every chemical laboratory. We are faced with a unique phenomenon that in the various expressions and instrumental solutions lays the foundations of knowledge and experience, on which much of the Mediterranean cultural heritage will be based.

Far from being conclusive, the research opens the door to various considerations, but what is obvious is that regardless of the evident knowledge of the distillation technique and the invention of a targeted instrumentation, wine, oil, wool, the different vascular types, flowers, plants, and aromas all seem to be actors of the same scenario, which becomes a decorative motif of any surface that can be painted, be it a vase or the walls of a room.

The phenomenon is also part of a particular scenario such as the Minoan, Mycenaean of the late second millennium BC, when art is expressed in the many shapes and colours of nature, testifying how deeply aesthetic pleasure is rooted in the Aegean society of the second millennium BC.paragrafo